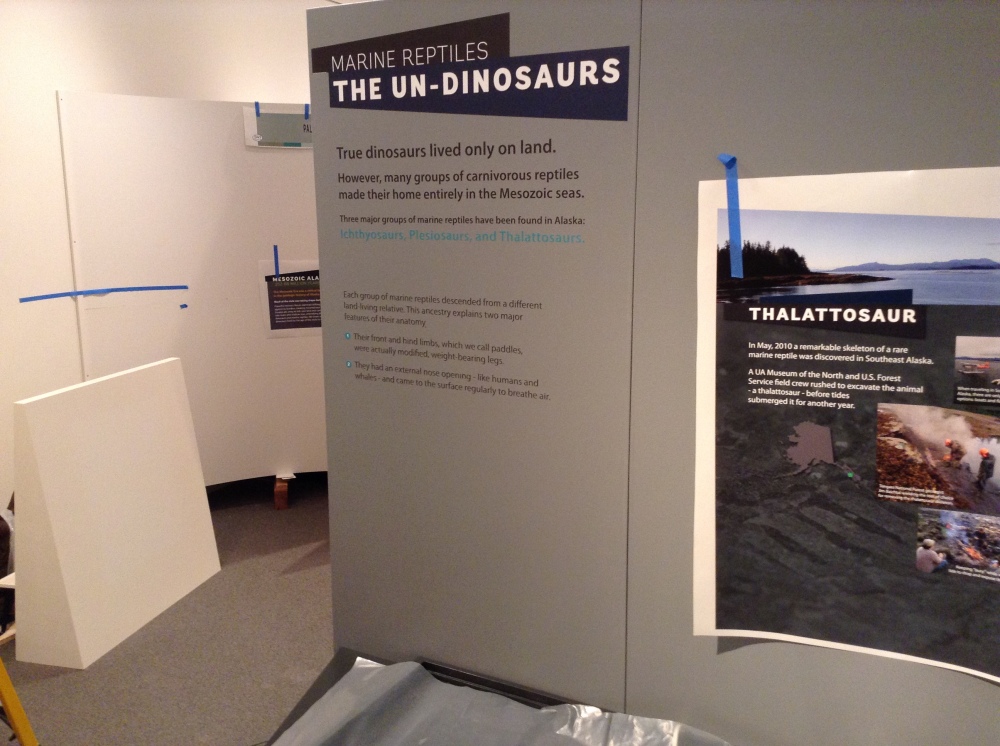

True dinosaurs lived on the land, but you can’t talk about ancient Arctic life without mentioning the many types of marine reptiles that made their home in the Mesozoic Era. Three major group of these carnivorous reptiles have been found in Alaska:

Icthyosaurs

Plesiosaurs

Thalattosaurs

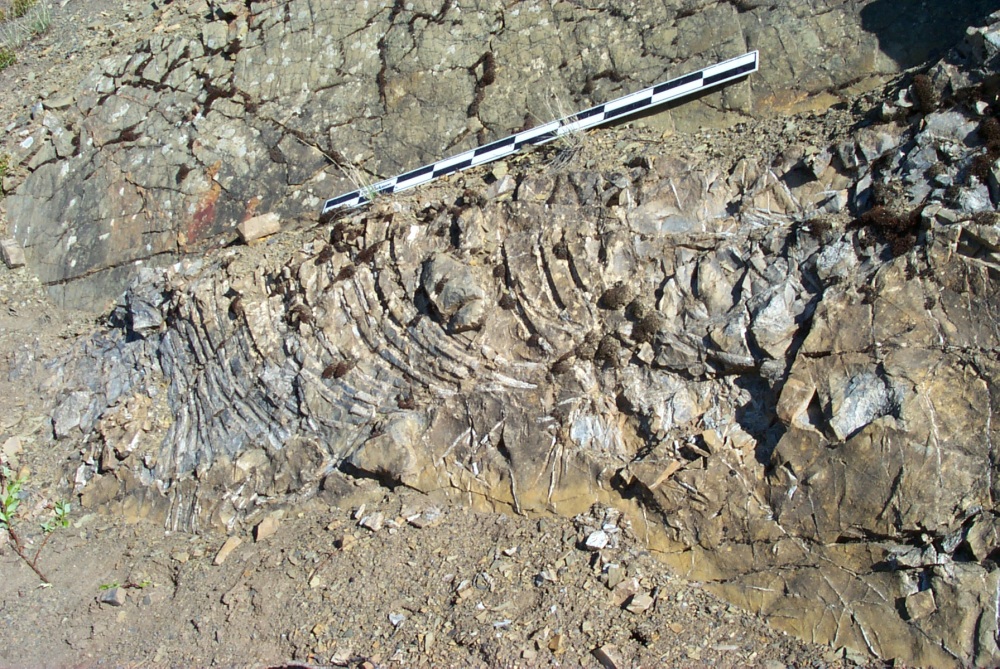

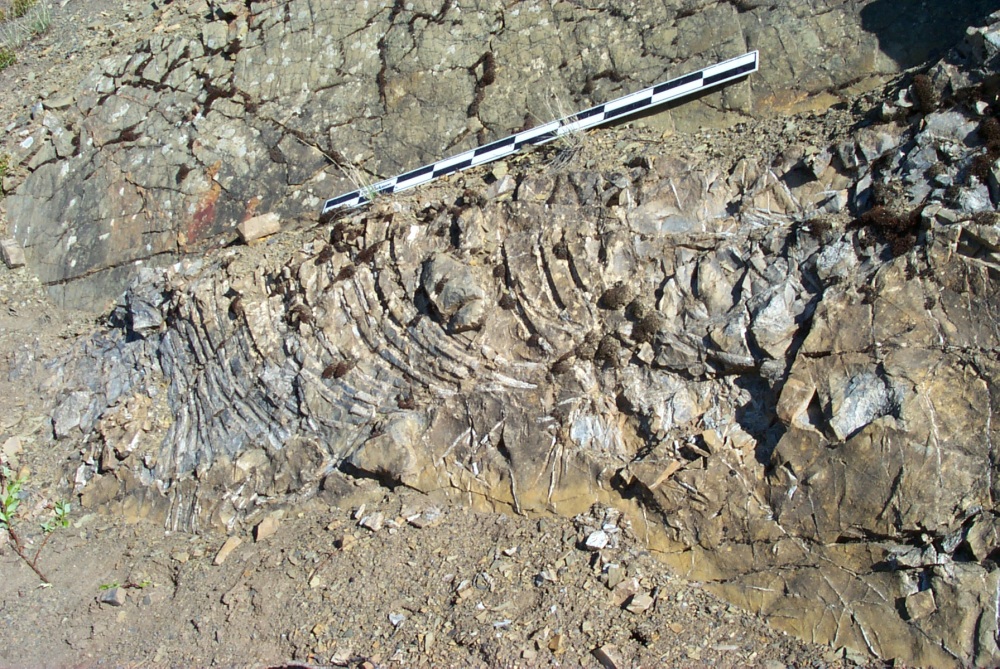

Ichthyosaur, on location. Specimen data: UAMES 2437; Name: Shastasauridae indet; Geological formation and age: Otuk Formation, Late Triassic, ~215 million years old; Diet: fish, ammonites; Body length: 7 m+ (~25 feet); Where found: Brooks Range foothills, northern Alaska

One of the best known specimens of ichthyosaur in Alaska was found on the North Slope almost seven decades ago. And it will be on permanent display for the first time in Expedition Alaska: Dinosaurs, opening May 23, 2015 in the museum’s Special Exhibit Gallery.

…

In 1950, a team from the U.S. Geological Survey mapping the U.S. Naval Petroleum Reserve in the western Brooks Range of Alaska stumbled on an amazing fossil – a 12-foot-long partial skeleton of a large marine reptile.

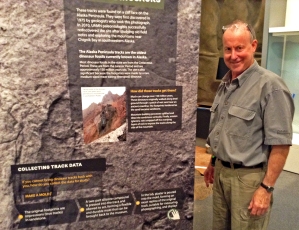

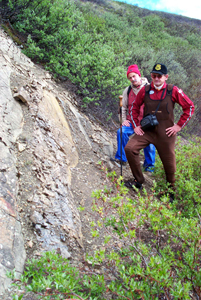

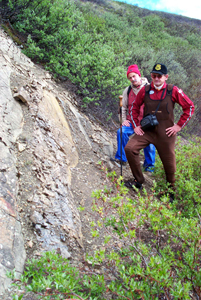

Carl Benson stands with the ichthyosaur fossil discovered in 1950 while mapping the US Petroleum Reserve.

Carl Benson, a retired geophysicist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks who was on the expedition, says they recognized it right away. “We knew what it was when we found it,” he said. “We talked about it in the tent that night and during the remainder of the field season.”

It was the only vertebrate specimen they found on their five-month survey, a geologic reconnaissance that completed the first mapping of the area. The team collected lots of fossils on the trip but didn’t have room for something that big. They did cart a huge amount of specimens and rock samples back to USGS headquarters, but the ichthyosaur was the only animal specimen they found from the Triassic period, about 210 million years ago.

Based on photographs, paleontologists at the University of Alaska Museum of the North identified the fossil as an ichthyosaur, a prehistoric marine reptile that resembled modern dolphins and whales. Because of the remoteness of the area, it would be more than 50 years before the fossil could be recovered and it would take another decade before research was completed.

…

They called it “Fishlift.” A team of Army soldiers and pilots, museum researchers, and a curious insect-like helicopter known as a Chinook set out on an expedition in the summer of 2002 to retrieve the ichthyosaur specimen.

Scientists knew that the animal lived 220 million years ago, a relic of the Triassic Period. It was the first specimen of its kind ever found in Alaska, and also the first articulated skeleton. Such an important find could not be left to the elements on the chance that the bluff could weather away, yet no museum researchers had been to the site since. The remote location and lack of a suitable landing area prevented it from being removed and preserved.

Former earth sciences curator Roland Gangloff (foreground) arranged to excavate the ichthyosaur fossil with the help of the U.S. Army.

Recovering the fossil was no small feat. Then-curator Roland Gangloff recruited the help of the “Sugar Bears,” the Army’s B Company, 4th Battalion, 123rd Aviation Regiment based at Fort Wainwright. As part of a training mission, they flew a CH-47D Chinook helicopter to the remote discovery site, 350 miles northwest of Fairbanks.

On arrival, the team, including the museum’s operations manager Kevin May, scoped out the area looking for the site where the marine reptile was originally found. After consultation, the crew spotted the rock formation. They hiked the short distance, scanning the horizon to get their bearings. On the ridge, behind a row of bushes, they found it. The ichthyosaur was in better shape than they had expected. It took five days to excavate the fossil.

After the museum crew had safely encased the fossil in a sturdy plaster jacket weighing about a ton, it was loaded into the helicopter and flown to Fairbanks.

The museum still owes a debt to the Sugar Bears crew. If it weren’t for their help, the fossil would still be sitting out there.

…

In a recent issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, UAMN earth sciences curator Pat Druckenmiller and his colleagues confirmed the identity of the skeleton as an ichthyosaur, making it the first one found in Alaska and also the largest and most complete specimen known from the state.

Druckenmiller estimates this particular marine reptile was nearly 30 feet long, a rare fossil discovery for the state. “Ichthyosaurs were amazing animals. The Alaskan specimen is a type called a shastasaurid, which includes the largest marine reptiles to have ever lived – some rivaled the size of living blue whales.”

Ichthyosaurs are also famous for having the largest eyeballs of any animal that ever lived—some were the size of basketballs.

“This particular animal died during the Triassic Period and settled to the floor of the sea that used to occupy the place where Alaska is now located. Since then, the bottom of that sea has been pushed up to form what we now call the Brooks Range.”

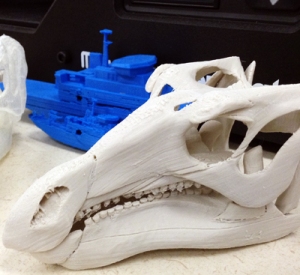

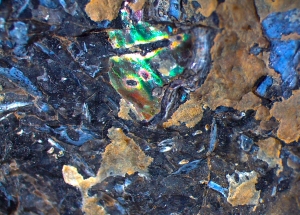

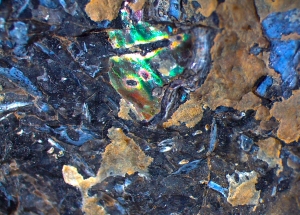

Close up view of the ichthyosaur gut contents showing iridescent mother-of-pearl fragments from an ammonite shell and bluish-gray bone fragments from a fish.

The fossil had other exciting stories to tell. While the specimen was being cleaned at the museum, researchers discovered an abundance of small, broken bones and shell fragments in the stomach region. “We found the last meals that this animal ate,” Druckenmiller said. “Finding gut contents in an ichthyosaur of this age is very rare and provides valuable insights into the diet and ecology of Triassic ichthyosaurs. This is especially interesting considering that some of these large animals may have lacked teeth.”

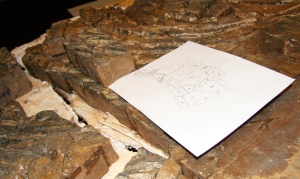

When he joined the museum staff in 2007, Druckenmiller was excited to find the ichthyosaur skeleton in the collection. “When we brought it out of storage, we began cleaning up the skeleton and could see the bones clearly for the first time.” The fossil took about a year to fully clean.

In the interim it’s been stored in the museum’s collection range. The chunks of rock have been removed for study and replaced many of times over so scientists could examine its last meal, among other investigations.

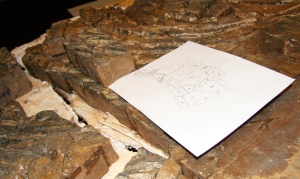

Collections Manager Julie Rousseau (left) and Curator Pat Druckenmiller complete the ichthyosaur puzzle for exhibit at the museum.

It looks like a giant jigsaw puzzle, with ribs and gut contents making up the myriad pieces. Displaying the ichthyosaur will be an additional challenge. Once the museum’s earth sciences crew puts the entire skeleton back together, the 25-feet long specimen will take up a large amount of floor space. The exhibit team is working to engineer a suitable platform so that visitors can get an up close look at this special specimen, one of only a handful of other identifiable ichthyosaurs known from Alaska. The northernmost occurrence of any well-preserved Triassic ichthyosaur in North America.

It looks like a giant jigsaw puzzle, with ribs and gut contents making up the myriad pieces. Displaying the ichthyosaur will be an additional challenge. Once the museum’s earth sciences crew puts the entire skeleton back together, the 25-feet long specimen will take up a large amount of floor space. The exhibit team is working to engineer a suitable platform so that visitors can get an up close look at this special specimen, one of only a handful of other identifiable ichthyosaurs known from Alaska. The northernmost occurrence of any well-preserved Triassic ichthyosaur in North America.

— Theresa Bakker, UAMN Marketing & Communication